Recently my mother was doing just that, and found an old issue of Heritage, the British history magazine, from February/March 1990. Naturally she saved it for me so that I could put it in my overburdened bookshelves...and while flipping through it, I ran across an article entitled “Pocock’s Flying Carriage”. The story was wonderful, and the name was familiar. Hmm, yes, we have met a Mr. Pocock before, haven't we...however, it seems to have been a different Mr. P.

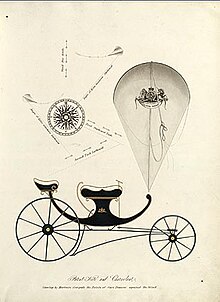

That Mr. Pocock (William) was, it seems, a London furniture-maker and known for his interest in patent furniture—designs that involved clever, ingenious mechanizations, as we saw with his Reclining Patent Chair. Perhaps there’s something to the name that dooms its bearers to be inveterate tinkerers, because another Mr. Pocock, this time a George, was inventing at the same time...and went far beyond furniture. You see, that Mr. Pocock was the proud inventor, in the 1820s, of the Charvolant, or Flying Car.

George P. (1774-1843) was a schoolmaster in Bristol who liked to invent things on the side. One of his inventions, a spanking machine (the “Royal Patent Self-acting Ferule”) which could punish several misbehaving schoolboys at once, had something to do with his teaching vocation (I wish I could find a picture of it!)...but evidently, Mr. Pocock was also fascinated by kites. He spent his youth experimenting with the power of kites, and induced a trusting friend to squat on a makeshift sled attached to kites. The friend ended up dragged away faster than George could follow on foot and was eventually tumbled into a quarry (uninjured, fortunately) but young George was even more hooked by kite power.

More experimentation followed, fortunately with no fatalities—that included launching his own daughter 300 feet into the air in a kite-drawn chair. Of course, you knew what would come next: kite-powered carriages. He spent several years working on his Charvolants, and finally in 1826 registered a patent. In 1828 he demonstrated a Charvolant at Ascot to King George IV, and was soon running demonstration races, beating the London coach in a race from Bristol to Marlborough by twenty-five minutes (after giving the coach a 15 minute head-start.) His Charvolant could travel as fast as twenty miles per hour, and the ride was much smoother and quieter than a horse-drawn vehicle—in fact, a Charvolant driver blew a bugle to warn vehicles it was overtaking, because of its quietness.

Charvolant travel was also much cheaper than travel utilizing horses: wind was free, after all, while horses were expensive to maintain and had to be changed on journeys of more than fifteen to twenty miles. And, amusingly, Charvolants could travel the turnpikes free. Tolls were charged at toll-gates based on the number of animals drawing any given vehicle...and Charvolants were notably draft animal-free. Though critics scoffed that a Charvolant would be grounded on a windless day, Mr. Pocock remained unruffled and replied, “Ships might be objected to on this principle—that there were sometimes calms, or contrary winds.”

Alas for Mr. Pocock, though, his timing was bad. Despite the interest his Charvolants generated, another new mode of transportation generated even more interest and would soon doom the Charvolant to a sidenote in transportation history: the railway.

How absolutely cool is that? I want one!

ReplyDeleteI want one too except I would probably get airsick! It sounds totally awesome.

ReplyDeleteI would love for someone to build a replica and see how it might handle modern highways!

ReplyDelete