Oh, I do love looking at Marissa’s fashion prints. And I admit to being a bit of a clothes horse. I can even use a sewing machine to good effect when needed. But I can only bow in admiration to the ladies who plied the needle in the nineteenth century.

Oh, I do love looking at Marissa’s fashion prints. And I admit to being a bit of a clothes horse. I can even use a sewing machine to good effect when needed. But I can only bow in admiration to the ladies who plied the needle in the nineteenth century.

You may see various terms for a seamstress. A lady with her own shop in Regency England, for example, might have been called a mantua-maker. Later, the lady was called a dressmaker. You would go to her, look through patterns, and be measured. She might have fabric, or, in some cases, you might bring your own. Once the dress had been pieced together, you might return for an additional fitting. Those with sufficient funds or who lived farther out from the city might pay for a lady to come to them for fittings.

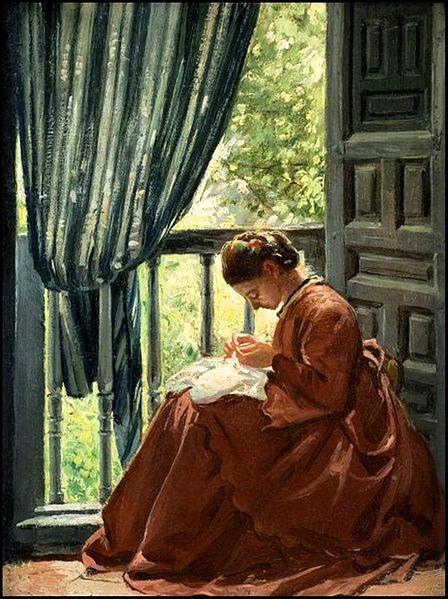

Inside the dressmaker’s shop, several ladies might be employed, all hand sewing every inch of those gorgeous dresses Marissa has been sharing with us. Some were allowed to work from home, picking up projects and returning them as they finished. As a needle worker, you might start with simple things like interior seams or hemming and graduate to more fancy work like embroidery. The hours were long, pay not much, and some seamstresses had trouble with eyesight in later years from toiling over a lamp or candle long into the night. Even in pioneer Seattle, the newfangled sewing machines were rare.

Inside the dressmaker’s shop, several ladies might be employed, all hand sewing every inch of those gorgeous dresses Marissa has been sharing with us. Some were allowed to work from home, picking up projects and returning them as they finished. As a needle worker, you might start with simple things like interior seams or hemming and graduate to more fancy work like embroidery. The hours were long, pay not much, and some seamstresses had trouble with eyesight in later years from toiling over a lamp or candle long into the night. Even in pioneer Seattle, the newfangled sewing machines were rare.

Sometimes dressmakers branched out to other areas. Such must have been the case for Mrs. Libby and Steele, who announced in the December 3, 1866, Puget Sound Weekly that they had opened an establishment on Commercial Street in Seattle. They claimed to have millinery, dress making, and ladies furnishings, including bonnets, hats, hoopskirts, ribbons, trimmings, and flowers, along with plain and fancy sewing done to order. Ladies of Seattle and the vicinity were invited to call. Note that the way the words MRS is written in the ad, it is unclear whether it was two misters or two ladies.

Nora Underhill, the heroine of my upcoming book, A Convenient Christmas Wedding, is a seamstress, one of the first in pioneer Seattle. She hasn’t the funds to set up her own shop, but she convinces one of the general mercantiles to allow her to work out of a corner. The customers buy the fabric and notions from the store and come to her for items to be made up.

That is, until Nora decides to buy herself a husband. More on that in November. :-)

2 comments:

I love the posts on Two Nerdy History Girls from the Mantua Makers at Colonial Williamsburg. I am in awe that people can still make a dress by hand! They made a dress in a day at midsummer last year. I read that men in the West were more interested in owning sewing machines than their eastern counterparts. It saved their wives labor and allowed farmers to keep up with the wealthy neighbors in fashion. I think I read an excerpt from the book Gender and Generation on the Far Western Frontier By Cynthia Culver Prescot.

I agree, QNPoohBear--sewing a dress by hand is not for the faint of heart! The wonderful reenactors at Fort Nisqually here make their own dresses by hand. You should see the tiny stitches, the fancy work. Amazing!

I had not heard that about sewing machines on the Western frontier, though I know the Factor at Fort Nisqually bought one for his wife. I'll have to look deeper on that. (Picture me muttering "lovely, lovely research.") Thanks!

Post a Comment