Our next destination on the Doyle family tour of southern England was the seaside town of Lymington, from which we planned to spend the next day visiting the Isle of Wight. “Ferry reservations?” we cluelessly trilled. “Who’ll be going to the Isle of Wight on a Thursday morning?”

Our next destination on the Doyle family tour of southern England was the seaside town of Lymington, from which we planned to spend the next day visiting the Isle of Wight. “Ferry reservations?” we cluelessly trilled. “Who’ll be going to the Isle of Wight on a Thursday morning?”Um...well, as it turned out, a lot of people. The ferry was book solid until 4 pm, which meant our plans to see Cowes and Queen Victoria’s Osborne House were shot. It was time for Plan B. And you know what? As much as I was bummed to miss Osborne House, Plan B wasn’t so bad...not when it included a visit to a handsome stately home, Beaulieu (that’s pronounced “Bew-lee”, just so you know).

In addition to the current house, Beaulieu includes the remains of a large medieval monastery (here's a section of garden with bits of original stonework that have been found) and some lovely plantings (I especially loved this laburnum tunnel...as did hundreds of bees!)

We also did a lot of driving around the New Forest, another royal hunting preserve (this time dating to the time of William the Conqueror). Though much smaller and tamer than Dartmoor, there were small moors, also inhabited by lots of sheep and ponies. And while wandering around a section of forest, I heard my first cuckoo call.

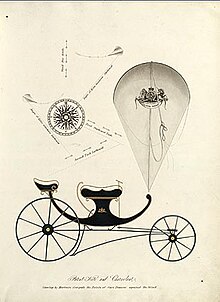

The next day we were off to another long-awaited destination: Brighton, home of the Prince Regent's beloved Pavilion, where he would spend the summer enjoying the breezes off the English Channel. He first discovered Brighton (or Brighthelmstone, its original name as noted in the Domesday Book) in the early 1780s, when sea-bathing had become the latest health fad. Prinny was charmed and bought a modest farmhouse, which he commissioned architect Henry Holland to turn into a home worthy of the Prince of Wales. Holland built him one...but evidently it wasn't grand enough, for in 1815 Prinny hired architect John Nash for an upgrade. And what an upgrade he got!

The exterior of the Pavilion is made of chastely cream colored stone, in a fantastical dreamlike Mughal style with onion domes, pierced screens, and minarets--rather a contrast to the Georgian classicalism that had been the prevailing building style in the town for the last fifty years. And while it's beautiful in a fanciful way, it's only the beginning.

The interior is, quite simply, jaw-dropping. Where Indo-Islamic style prevails on the outside, within the decor is fantasy Chinese. There are dragons everywhere (include one of silver gilt clinging to the chandelier in the Banqyueting Room that must be at least ten feet long). In the Music Room, the central done is covered with hundreds of thousands of gilt cockles shells, which look like dragon scales. The colors are rich and saturated, and every surface is decorated; even the kitchens, which were state of the art in 1820, are beautiful.

What's even cooler about the Pavilion, though, is its history. After Prinny's (now King George IV) death in 1830, his brother King William used the Pavilion. But when Victoria came to the throne, she was not amused by the Pavilion and by Brighton in general, finding it far too crowded and the palace itself too small and lacking in privacy. She bought land on the Isle of Wight for her summer retreat of Osborne House, and the Pavilion was sold to the city of Brighton (after Victoria carried off anything that wasn't nailed down.) Decades of decline followed; Nash's creation was not built to last. But after World War I, partly spurred by the interest of Queen Mary (who began to donate back to the Pavilion things that Victoria had carried off) and a full-scale restoration of the Regency era palace was begun, hugely helped by the fact that all of Nash's original plans and detailed paintings of the rooms were available. Since then, despite fires and other calamities, work has been ongoing, and the result is just breathtaking. We sure as heck enjoyed it! If you ever, ever have a chance to see it--go!

Our hotel was also worth mentioning; Brighton remained a popular watering hole long after Prinny went to the great Assembly Room in the sky, and a series of elegant hotels were built right along the shore, rather like a Victorian Miami Beach. The grand Brighton was indeed a grand old place, a little shabby in spots but oh so atmospheric. We ate dinner at the Old Ship Hotel, mentioned in at least one Georgette Heyer novel that I remember, and then after dark looked out at the Brighton Pier, which is basically a small amusement park built over the water (it dates to 1899) before going to sleep for the last night of our trip.

The last installment: Hampton Court Palace, and where I'm going next time!