Poyais.

Never heard of it? According to its guide for immigrants, it was a paradise. The 8,000,000-acre Republic of Poyais lay along the Caribbean. Its capital city, St. Joseph, had tree-lined streets, mansions, and an opera house. It was the center of culture and elegance. The fields surrounding it would grow any manner of food, three crops a year. The oceans in front of it teemed with fish. The mountains at its back were so filled with gold and gems that one might merely bend to pick them up.

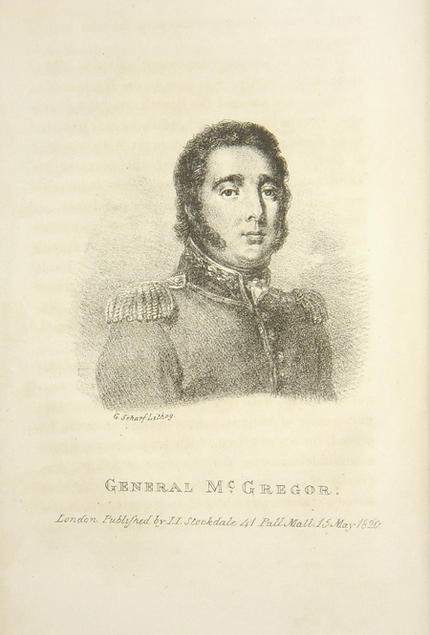

Better yet to the people of nineteenth century England, its Cazique (leader) was a decorated hero of the Napoleonic Wars! Colonel (or General, depending on who was his biographer) Gregor MacGregor had gone on to fame in South America, fighting battles for independence there. He was said to have been given charge of his own country in thanks for his services to the king of Mosquito Coast: Poyais.

So when the colonel arrived in London in 1821, graciously seeking investment and immigrants for his new country, hundreds jumped at the chance. Banks offered him loans in astronomical amounts for that time (as high as a quarter of a million pounds). The gentry feted him in their homes. Would-be settlers quit their jobs, sold all they owned, cashed in their savings for notes from the Royal Bank of Poyais, and prepared to set sail. They had been promised positions like clerk, military leader, or banker in the new government. A few had been given titles. They had paid for lands on which to farm or ranch. More than 250 left on two vessels in September 1822.

Only 50 ever made their way back to England.

You see, Poyais didn’t exist.

The first settlers arrived to find no city, no country, no anything! A storm ended up sending their ships back out to sea for safety, stranding them on an inhospitable shore. Most died from sickness or starvation. The king of the Mosquito Coast denied he had ever given MacGregor a kingdom. A few hardy souls stayed in neighboring countries, and the other survivors ultimately found their way back to England in October 1823.

Amazingly, many refused to blame Colonel MacGregor! They were certain they’d simply mistaken their way and that Poyais was out there somewhere, beyond the horizon. They blamed the captains of the ships and MacGregor’s agents, who had come with them, for misleading them.

MacGregor swore he was innocent, but he still fled from England to France, where he continued his scheme. He was arrested in 1825 and tried for his crimes but gave such a passionate defense that he was acquitted. He retired to South America and lived out his life in style, though not in his beloved Poyais.

It seems even he could not find his way back to it.

_SCAM.jpg)

.jpg)