Pardon me for jumping the gun by a couple days, but Marissa and I will be on vacation next week, so I couldn’t post the July amusements then, and we have something special planned for the week of the July 10—the launch of The Captain’s Courtship! Please come back for games, prizes, and a general good time! And if you’re looking for something to do on Tuesday, July 3, please stop by the Love Inspired Historical Group on Goodreads and join me for a special Q&A session on the book.

And now onto the various ways young ladies and gentlemen could find to amuse themselves in the great metropolis of London in July.

Amusements, alas, are starting to thin, for the Season begins to wind down in earnest in July. The Drury Lane and Covent Garden theatres often closed for the season in June, and the Opera House closed in July. The British Museum closed the end of July and didn’t open again until October. And for many years, the King (or Prince) closed the Parliamentary session sometime in July or early August, leaving the aristocracy less reason to stick around, particularly as their more palatial, cooler, more comfortable country houses beckoned.

But if your papa was one to stay in London all year, by virtue of his profession or inclination, you still might find some things to entertain you. For example, mighty ocean-going ships were often launched during the summer months. You might see the advertisement in the newspaper and hasten down to Deptford to watch the behemoth slide into the Thames for the first time. The ships all turned out to congratulate the newcomer, as it were, flags flying. Quite the spectacle!

But even more popular were the cricket matches at Lord’s, where admission could be had for about 1 shilling. Cricket had already gained a loyal following by the nineteenth century, with club teams and professional teams flourishing. You see, young men learned cricket at school and university. They naturally wished to keep playing when they left those hallowed halls. Many joined cricket clubs, where they played against other clubs for fun. Part of that fun, it seems, involved considerable side gambling. According to the Lord’s website, more than 20,000 pounds was bet on one game alone!

Lord’s Cricket Grounds came into being when the Marylebone Cricket Club members found their games being thronged with riffraff. Seeking exclusivity, they asked Thomas Lord, who played for the White Conduit Cricket Club, to find them a private ground. The Lord’s Grounds were moved twice before settling in the place we know today. Yet the crowds followed them, requiring the construction of a pavilion and refreshment stalls. Between matches, sheep were allowed to graze on the grass to keep it at a short length.

Two of the more eagerly anticipated matches were the Eton versus Harrow match, with young gentlemen from those schools taking part, and the Gentlemen versus the Players matches. This second type of match involved a team of players from the cricket clubs competing against players from professional cricket teams. The cricket club players all came from the aristocracy, gentry, or upper-level professions such as physicians or barristers. The professional players generally came from middle or lower-class backgrounds. Crowds were huge, competition fierce, and games often went on for three days!

And some people think major league baseball is thrilling!

Friday, June 29, 2012

Tuesday, June 26, 2012

Another Miscellany, Actually

These Miscellanies are catching!

First, the important (and fun!) part of this week’s Miscellany: the winner of the drawing for the ARC of Courtship and Curses is mfantaliswrites! Mfantaliswrites, please contact me via my website so that we can arrange getting your book to you.

Second: as we step into summer, our posting schedule at Nineteenteen will shift around a bit (as it usually does). We’ll be taking a couple of vacation weeks (including next week over the Independence Day holiday) and weeks in August to ferry some of our respective offspring off to college…but on the fun side, Regina and I will each be having a book launch event and we’ll do our customary blogging from the Romance Writers of America National Conference where we have our annual get-to-spend-time-together holiday. So there’s some fun stuff to look ahead to over the summer months.

Third: I’m launching a new series! Since we completed the series of brief biographies of Queen Victoria’s nine children, I thought it might be fun to do an occasional series on some of her grandchildren as well.

As a result of having nine children, the Queen ended up with quite a respectable crop of grandchildren: forty-two, in fact, though it is thought she probably had a least a few illegitimate ones that she was not informed of. Here are a few interesting statistics about them, presented in the form of a quiz--do you know their identities? (answers will be posted in the comments column):

As a result of having nine children, the Queen ended up with quite a respectable crop of grandchildren: forty-two, in fact, though it is thought she probably had a least a few illegitimate ones that she was not informed of. Here are a few interesting statistics about them, presented in the form of a quiz--do you know their identities? (answers will be posted in the comments column):

First, the important (and fun!) part of this week’s Miscellany: the winner of the drawing for the ARC of Courtship and Curses is mfantaliswrites! Mfantaliswrites, please contact me via my website so that we can arrange getting your book to you.

Second: as we step into summer, our posting schedule at Nineteenteen will shift around a bit (as it usually does). We’ll be taking a couple of vacation weeks (including next week over the Independence Day holiday) and weeks in August to ferry some of our respective offspring off to college…but on the fun side, Regina and I will each be having a book launch event and we’ll do our customary blogging from the Romance Writers of America National Conference where we have our annual get-to-spend-time-together holiday. So there’s some fun stuff to look ahead to over the summer months.

Third: I’m launching a new series! Since we completed the series of brief biographies of Queen Victoria’s nine children, I thought it might be fun to do an occasional series on some of her grandchildren as well.

As a result of having nine children, the Queen ended up with quite a respectable crop of grandchildren: forty-two, in fact, though it is thought she probably had a least a few illegitimate ones that she was not informed of. Here are a few interesting statistics about them, presented in the form of a quiz--do you know their identities? (answers will be posted in the comments column):

As a result of having nine children, the Queen ended up with quite a respectable crop of grandchildren: forty-two, in fact, though it is thought she probably had a least a few illegitimate ones that she was not informed of. Here are a few interesting statistics about them, presented in the form of a quiz--do you know their identities? (answers will be posted in the comments column):- Her eldest grandchild was born in 1859 when she was not quite 40, less than two years after the birth of her last child in 1857.

- Her last grandchild was born in 1891, just ten years before her death; he himself would die in 1914, fighting against his cousin.

- And though the queen outlived several of her grandchildren—don’t forget that the high infant mortality of the 19th century was still an issue even among royalty—her final surviving grandchild lived until 1981, dying at age 98, just a few month before the wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer.

Friday, June 22, 2012

The Grand Tour, Part 8: The Romance of Venice

We are on our second week in Italy, with sun-drenched days and sultry nights. Oddly enough, we’ve nearly reached a surfeit of ancient sculptures (another Venus missing some part of her anatomy, anyone?), classical paintings (why are the men mostly clothed and the women naked?), and Roman architecture (how many aqueducts does a girl need to see in her lifetime?). Likewise, the carriage is no longer such a delightful sight each morning. And I don’t know about you, but that one women in our group is truly starting to overstretch my nerves!

We are on our second week in Italy, with sun-drenched days and sultry nights. Oddly enough, we’ve nearly reached a surfeit of ancient sculptures (another Venus missing some part of her anatomy, anyone?), classical paintings (why are the men mostly clothed and the women naked?), and Roman architecture (how many aqueducts does a girl need to see in her lifetime?). Likewise, the carriage is no longer such a delightful sight each morning. And I don’t know about you, but that one women in our group is truly starting to overstretch my nerves! For all these reasons, Venice is a delightful break in our routine. We leave the carriages at Mestré and embark in a hired gondola for a two-hour cruise to the city. And what an amazing city it is, rising, it seems, like Venus from the very sea! Our handsome gondolier flexes his muscles as he explains how the city is a series of little islands linked by bridges and interconnected with canals. He is delighted to tour us through several of the canals, and right under a lovely enclosed limestone bridge. Hard to believe our own Lord Byron named this the Bridge of Sighs, for it used to lead from the prisons to the Doge’s inquisition rooms. Legend has it that if two lovers kiss underneath it at sunset they will find eternal love.

For all these reasons, Venice is a delightful break in our routine. We leave the carriages at Mestré and embark in a hired gondola for a two-hour cruise to the city. And what an amazing city it is, rising, it seems, like Venus from the very sea! Our handsome gondolier flexes his muscles as he explains how the city is a series of little islands linked by bridges and interconnected with canals. He is delighted to tour us through several of the canals, and right under a lovely enclosed limestone bridge. Hard to believe our own Lord Byron named this the Bridge of Sighs, for it used to lead from the prisons to the Doge’s inquisition rooms. Legend has it that if two lovers kiss underneath it at sunset they will find eternal love.We are already in love with this city! Who cares that a rather noxious order is rising from these waters as the day turns to evening? Our gondolier brings us right up to the steps of a charming little hotel with balconies overlooking the Grand Canal, and porters ferry our baggage up to our rooms.

Oh, but it’s difficult to sleep tonight! From the balcony we can see the moon kissing its wavering reflection in the waters, and someone is singing, deep and low. Do we dare slip out into the velvet night? Perhaps find one of Venice’s famed masquerades? But no! Our chaperone is also awake and far too diligent. So, it’s off to bed to dream of handsome courtiers and masked balls.

In the morning, we set off to explore the city, starting with a tour of the Basilica of San Marco, looking a bit like an Eastern potentate’s castle with its domes and cupolas. Marissa points out that it reminds her of the Prince’s Brighton Pavilion back home.

But this pavilion is far more steeped in history. The eight columns on the outside are said to have been captured from Constantinople but originated in the very Temple of Jerusalem. The four massive brass horses are also said to have once graced the Chariot of the Sun.

Through the gates of Corinthian brass, the interior is covered with mosaics and paintings on walls, floors and the curving gilded ceilings. Our necks are soon stiff from all our gazing.

Will you climb the Campanile, the tall tower at the edge of the piazza with me? Oh, good! We lift our skirts and start up the stone steps. My but we are breathless when we reach the top. And Mrs. Starke said it was an easy climb! But the view, out over the entire city and the waters surrounding it, is magnificent! Good thing those two scholars from Verona were willing to help us on the way down. And they invited us to a masquerade this evening! I adore the way he kissed your hand on parting. Sigh!

My heart is all a-flutter. Should we try to escape our chaperone and go?

Tuesday, June 19, 2012

A Miscellany… and another chance to win!

June 19 is rather an interesting day in history—not for itself (though I see, through a brief internet search, that today is the 476th anniversary of Anne Boleyn’s beheading and the 164th anniversary of the opening of the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, NY) but because it falls between two very interesting days. One hundred ninety-seven years ago yesterday, on June 18, 1815, Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte fell for the last time to the combined forces of England, Prussia, and the Netherlands at the Battle of Waterloo…

And one hundred seventy-five years ago tomorrow, on June 20, 1837, King William IV of England died (after hanging tenaciously to life in order to see another Waterloo Day celebrated in England--his words to his doctor were, " Doctor, I know I am going, but I should like to see another anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo. Try if you cannot to tinker me up to last out that day.") and his niece Victoria became queen at 18. An eventful few days, don’t you think?

And now for something completely different…introducing My Shiny New Website, courtesy of Barry Holt at Three Doors Up Multimedia. I adore the heading Barry created from my beloved collection of fashion prints…and as it’s on Wordpress, I’ll be able to do a much better job of keeping it updated. What do you think?

And finally…one last chance to win an ARC of Courtship and Curses. Alas, I have no mystery objects lined up, so we’ll take it easy this time around (it is, after all, the eve of the Solstice and official start of summer...another important date!) and I’ll draw a winner from among all comments left on this post through next Monday night. Shipping to North American addresses only, please.

And finally…one last chance to win an ARC of Courtship and Curses. Alas, I have no mystery objects lined up, so we’ll take it easy this time around (it is, after all, the eve of the Solstice and official start of summer...another important date!) and I’ll draw a winner from among all comments left on this post through next Monday night. Shipping to North American addresses only, please.Happy June 19th!

Tuesday, June 12, 2012

They're Everywhere!

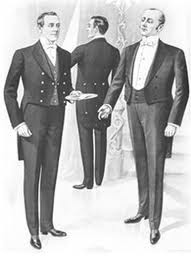

In fiction about the 19th century, you see them everywhere: they’re carrying tea trays, opening doors, serving dinner, or wandering about decoratively at balls wearing powdered wigs and knee-breeches with silk stockings. I’m referring, of course, to footmen.

In fiction about the 19th century, you see them everywhere: they’re carrying tea trays, opening doors, serving dinner, or wandering about decoratively at balls wearing powdered wigs and knee-breeches with silk stockings. I’m referring, of course, to footmen.Footmen were the main type of indoor male servant: any household with any pretension to gentility kept at least one footman. Do you remember, in Pride and Prejudice, how Lady Catherine de Bourgh is surprised to hear that Lizzie’s uncle keeps a manservant? A footman cost much more to maintain than a maid, though many of their duties could and did overlap: a footman earned more, and was generally supplied with a few different uniforms (called ‘livery’) for different occasions, which could be expensive.

So what did a footman do? His duties might vary from household to household, according to The Complete Servant, first published in 1825, but the basic ones were listed as the cleaning of knives, shoes, plate (silver), lamps, and furniture; the laying and replenishing of fires, answering the door, going on errands, waiting at table, and answering the parlor bell. A footman rose early to get a head-start on these duties, because he would be expected to set the table for, and serve breakfast for his employers. After tidying up the breakfast parlor, he might be sent out to deliver notes and invitations, then be back to finish any tasks he hadn’t already, and then perhaps be ready to accompany the lady of the family while she paid calls—it was the footman’s job to do the actual delivery of calling cards—or accompany her while shopping to carry parcels and open doors. Here’s a delicious bit from The Complete Servant: “In going out with the carriage, the footman should be dressed in his best livery, his shoes and stockings being very clean, and his hat, great coat, &c. being very well brushed; nothing being so disgraceful as a slovenly exterior. He should be ready at receiving directions at the carriage door, and accurate in delivering them to the coachman, and though he may indicate the importance of his family by his style of knocking at a door, he ought to have some regard to the nerves of the family and the peace of the neighborhood.” Hmm—I wonder if they sometimes got a little carried away?

Then there would be setting the table for dinner and serving it under the butler’s watchful eye, sneaking down to the parlor while the family dined to make sure the fire was replenished, the lamps lit, and the sofa cushions plumped up. He helped the butler clean and put away any plate that was used at the meal, carried up the evening tea-tray (customary earlier in the century), made sure candlesticks were ready when family members were ready to retire up to bed.

Because they occupied such a public place in the household, good looks were definitely an asset to a footman, especially height—everyone wanted footmen who were at least six feet in height, because they looked so imposing when in dress livery—and a fine calf to the leg (ditto the dress livery, which usually included knee-breeches and silk stockings). In fact, ads in 19th century papers from footmen looking for positions generally included their height, so that potential employers could “match” them to existing staff members!

A footman’s career tended to be a short one, relatively speaking, as they often moved on: an ambitious footman might aspire to an underbutler’s or butler’s position some day, or perhaps to a valet’s. Or if he decided not to remain in service, he might open an inn or tavern. The heyday of the footman ended with the first world war, when most of them enlisted; it was a traumatic moment for some old-fashioned aristocrats to have maids serving at table rather than the imposing, liveried footmen they were used to.

Friday, June 8, 2012

Public Spectacles, Amusements, and Objects Deserving Notice, June

June was the middle of the Season in London during the nineteenth century. Everyone who was anyone was in town, enjoying weather that tended to be more often on the pleasant side. And they had many choices for outdoor entertainments. For example, Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens generally opened in early June in the earlier part of the century, horse races popped up around the country, and the Thames was full of rowing matches and sailing regattas.

But the big event for most of the first two decades of the century was His Majesty’s birthday celebration, centered around June 4th. Even though George III was growing stranger and his son would end up the Regent and later king, every major city in England, many small hamlets, and every territory and embassy world-wide held events on the King’s birthday.

In London, tradesmen with royal warrants illuminated their shops in the evening. Special illuminations (painted panels with lanterns behind and between them) glowed in public places as well. Mail coaches paraded from the Post Office to the St. James’s Palace and back. Famous composers and musicians held concerts. The King’s Master of Music on occasion even composed a new Ode for the celebration (although that was falling out of favor). Those of particularly high rank and favor were invited to a grand drawing room at the palace.

In London, tradesmen with royal warrants illuminated their shops in the evening. Special illuminations (painted panels with lanterns behind and between them) glowed in public places as well. Mail coaches paraded from the Post Office to the St. James’s Palace and back. Famous composers and musicians held concerts. The King’s Master of Music on occasion even composed a new Ode for the celebration (although that was falling out of favor). Those of particularly high rank and favor were invited to a grand drawing room at the palace. On the Thames, rowing matches and regattas brought out the boats. Areas of the country where garrisons were stationed held military reviews; ports held naval maneuvers. Church bells rang throughout the nation. Can you tell it was a party? The English loved their “Farmer George”!

Now, more than 200 years later, one organization still celebrates. The students at Eton commemorate the birthday of George III with special lectures, cricket

Now, more than 200 years later, one organization still celebrates. The students at Eton commemorate the birthday of George III with special lectures, cricket matches, and a procession of boats on the river. According to the school, no monarch except the Founder (Henry VI) was more involved and took more pride in the school. Eton is located near Windsor Castle, and apparently George III invited students to visit from time to time and was known to pop into the school for a visit whenever he was passing nearby.

May your June be as memorable!

P.S.—I will be taking a short break next week, so look for a post from Marissa on Tuesday, but no post from me until June 22.

Tuesday, June 5, 2012

The First Diamond Jubilee

This week Britons around the world are celebrating the 60th anniversary of Queen Elizabeth II’s accession. I’ve had fun watching the coverage on TV these last few days while exercising merrily away on the elliptical machines at my gym. I’m sure you must have heard at some point that this is only the second Diamond Jubilee for a British monarch in the thousand-year history of the kingdom…the first being that for, of course, Queen Victoria.

Victoria celebrated her Diamond Jubilee in June 1897, when she was a frail 78 (she would live three and a half more years, until 1901.) But her frailty didn’t keep her from being pleased to have beaten the record-length reign of a previous monarch—that of her grandfather, King George III, who was on the throne for 59 years and 96 days. Nor would it keep her from celebrating in a suitable fashion—she was much more amenable to appearing in public than she had been for her Golden Jubilee ten years before, when she had to be more or less bullied into joining the celebrations or even dressing up a bit for the occasion—indeed, one of her sons had to tell her, "Now, mother. You must have something really smart."

Victoria celebrated her Diamond Jubilee in June 1897, when she was a frail 78 (she would live three and a half more years, until 1901.) But her frailty didn’t keep her from being pleased to have beaten the record-length reign of a previous monarch—that of her grandfather, King George III, who was on the throne for 59 years and 96 days. Nor would it keep her from celebrating in a suitable fashion—she was much more amenable to appearing in public than she had been for her Golden Jubilee ten years before, when she had to be more or less bullied into joining the celebrations or even dressing up a bit for the occasion—indeed, one of her sons had to tell her, "Now, mother. You must have something really smart."

By 1897, her feelings had changed; her cabinet, in particular Joseph Chamberlain, Secretary of State for the Colonies, wanted to use the occasion of her Diamond Jubilee as a way to celebrate Britain’s mighty empire, and the Queen was happy to join in. Representatives from everywhere—from Australia to Zanzibar—were in attendance to celebrate with her.

Since the actual anniversary of her accession was on a Sunday (June 20), it was decided that the major public celebration would be held instead on the following Tuesday. Sunday was given to a Thanksgiving service in Windsor, and on Monday the Queen traveled to London to ready herself for the next day.

At 11:15 am on the 22nd she set out in an open carriage drawn by eight cream-colored horses, accompanied by her daughter Princess Helena and Alix, the Princess of Wales. Though the day had been overcast, according to accounts the sun broke through the clouds as she set forth, in a display of what had come to be called Queen’s Weather (so called as it never seemed to rain on her parades!) Though she wore her customary black, it was very elegant: "black silk, trimmed with panels of grey satin veiled with black net and some black lace", with a bonnet "trimmed with creamy white flowers and white aigrette"—no chiding required from her children! She was as eager to see the bystanders as they were to see her, though disconcerted by the shouts of "Steady, old lady! Whoa, old girl!" from one of the members of her household, Lord Dundonald, who rode just behind her carriage. It was some time before she realized he was addressing his horse, not her!

Her carriage drew up in front of St. Paul’s cathedral, where a brief service was held in front, so that she would not have to leave her carriage and manage the stairs on her tottery legs. Her procession crossed London Bridge and drove through parts of the poverty-stricken East End, then crossed back over Westminster Bridge and eventually down the Mall back to Buckingham Palace. Though it was almost too warm and sunny—the Queen was forced to take cover under a parasol—warmer still was the mood of the crowd, so that Victoria was moved to tears. Afterward, as she wrote in her journal, no one had ever "met with such an ovation as was given me, passing through those six miles of streets. The crowds were quite indescribable, and their enthusiasm truly marvellous and deeply touching. The cheering was quite deafening and every face seemed to be filled with real joy."

Other events followed over the next few weeks, including a military review, an address from Parliament, a couple of garden parties at Buckingham Palace, and a party for schoolchildren in Hyde Park.

Other events followed over the next few weeks, including a military review, an address from Parliament, a couple of garden parties at Buckingham Palace, and a party for schoolchildren in Hyde Park.

Among my collection I have this item pictured above: a commemorative mug celebrating the Diamond Jubilee, labeled "Presented by Henry Ponking, Mayor of Wallingford 1897". It’s fun to have a tiny piece of history; I may need to get myself a Jubilee mug from 2012 to go with it.

Felicitations, Your Majesty!

Victoria celebrated her Diamond Jubilee in June 1897, when she was a frail 78 (she would live three and a half more years, until 1901.) But her frailty didn’t keep her from being pleased to have beaten the record-length reign of a previous monarch—that of her grandfather, King George III, who was on the throne for 59 years and 96 days. Nor would it keep her from celebrating in a suitable fashion—she was much more amenable to appearing in public than she had been for her Golden Jubilee ten years before, when she had to be more or less bullied into joining the celebrations or even dressing up a bit for the occasion—indeed, one of her sons had to tell her, "Now, mother. You must have something really smart."

Victoria celebrated her Diamond Jubilee in June 1897, when she was a frail 78 (she would live three and a half more years, until 1901.) But her frailty didn’t keep her from being pleased to have beaten the record-length reign of a previous monarch—that of her grandfather, King George III, who was on the throne for 59 years and 96 days. Nor would it keep her from celebrating in a suitable fashion—she was much more amenable to appearing in public than she had been for her Golden Jubilee ten years before, when she had to be more or less bullied into joining the celebrations or even dressing up a bit for the occasion—indeed, one of her sons had to tell her, "Now, mother. You must have something really smart."By 1897, her feelings had changed; her cabinet, in particular Joseph Chamberlain, Secretary of State for the Colonies, wanted to use the occasion of her Diamond Jubilee as a way to celebrate Britain’s mighty empire, and the Queen was happy to join in. Representatives from everywhere—from Australia to Zanzibar—were in attendance to celebrate with her.

Since the actual anniversary of her accession was on a Sunday (June 20), it was decided that the major public celebration would be held instead on the following Tuesday. Sunday was given to a Thanksgiving service in Windsor, and on Monday the Queen traveled to London to ready herself for the next day.

At 11:15 am on the 22nd she set out in an open carriage drawn by eight cream-colored horses, accompanied by her daughter Princess Helena and Alix, the Princess of Wales. Though the day had been overcast, according to accounts the sun broke through the clouds as she set forth, in a display of what had come to be called Queen’s Weather (so called as it never seemed to rain on her parades!) Though she wore her customary black, it was very elegant: "black silk, trimmed with panels of grey satin veiled with black net and some black lace", with a bonnet "trimmed with creamy white flowers and white aigrette"—no chiding required from her children! She was as eager to see the bystanders as they were to see her, though disconcerted by the shouts of "Steady, old lady! Whoa, old girl!" from one of the members of her household, Lord Dundonald, who rode just behind her carriage. It was some time before she realized he was addressing his horse, not her!

Her carriage drew up in front of St. Paul’s cathedral, where a brief service was held in front, so that she would not have to leave her carriage and manage the stairs on her tottery legs. Her procession crossed London Bridge and drove through parts of the poverty-stricken East End, then crossed back over Westminster Bridge and eventually down the Mall back to Buckingham Palace. Though it was almost too warm and sunny—the Queen was forced to take cover under a parasol—warmer still was the mood of the crowd, so that Victoria was moved to tears. Afterward, as she wrote in her journal, no one had ever "met with such an ovation as was given me, passing through those six miles of streets. The crowds were quite indescribable, and their enthusiasm truly marvellous and deeply touching. The cheering was quite deafening and every face seemed to be filled with real joy."

Other events followed over the next few weeks, including a military review, an address from Parliament, a couple of garden parties at Buckingham Palace, and a party for schoolchildren in Hyde Park.

Other events followed over the next few weeks, including a military review, an address from Parliament, a couple of garden parties at Buckingham Palace, and a party for schoolchildren in Hyde Park.Among my collection I have this item pictured above: a commemorative mug celebrating the Diamond Jubilee, labeled "Presented by Henry Ponking, Mayor of Wallingford 1897". It’s fun to have a tiny piece of history; I may need to get myself a Jubilee mug from 2012 to go with it.

Felicitations, Your Majesty!

Friday, June 1, 2012

Guest Blogger Y.S. Lee: The London Foundling Hospital

We're happy to welcome Y.S. Lee back today!

When I lived in London, I walked past Coram’s Fields every day. It’s a beautiful park with a fountain, an urban farm (the sheep always look grimy, but London is a highly polluted city!), a ton of open space, and high gates. Most enticing of all to a curious adult is the sign saying, NO ADULTS UNLESS ACCOMPANIED BY A CHILD. I had to find out more, and since I didn’t know any children I could borrow at the time, it had to be theoretical research.

After basic details about the current park (www.coramsfields.org/), I learned that Coram’s Fields stands on the site of the old London Foundling Hospital – not a hospital in the modern sense of the word, but a charity orphanage. In the 1730s, sea captain, merchant, and philanthropist Thomas Coram became appalled by the number of homeless, dying, and dead children on the streets of London. There was no institution in England doing anything for illegitimate children – the usual reason for abandoning an infant to the workhouse or the streets. Coram persuaded George II to grant him a Royal Charter to establish a “hospital for the maintenance and education of exposed and deserted young children”. In 1741, the London Foundling Hospital opened in a temporary house and began accepting children. (Image above from the Foundling Hospital's website, http://www.foundlingmuseum.org.uk/)

After basic details about the current park (www.coramsfields.org/), I learned that Coram’s Fields stands on the site of the old London Foundling Hospital – not a hospital in the modern sense of the word, but a charity orphanage. In the 1730s, sea captain, merchant, and philanthropist Thomas Coram became appalled by the number of homeless, dying, and dead children on the streets of London. There was no institution in England doing anything for illegitimate children – the usual reason for abandoning an infant to the workhouse or the streets. Coram persuaded George II to grant him a Royal Charter to establish a “hospital for the maintenance and education of exposed and deserted young children”. In 1741, the London Foundling Hospital opened in a temporary house and began accepting children. (Image above from the Foundling Hospital's website, http://www.foundlingmuseum.org.uk/)

It must have been a tragic process: parents brought their children, usually babies under one year old, along with a distinguishing item - a trinket, ribbon, or meaningful scrap of writing – that was kept with the child’s record in case the parent came back to reclaim the child. I can’t help imagining a parade of destitute adults, hoping to give their children a decent chance at life by giving them up (maybe temporarily) to the Foundling Hospital.

The demand for the Hospital’s services was enormous – so much so that it was forced to turn away unknown numbers of children. In 1756, the House of Commons resolved that all children should be accepted – not just from London, but all over the country. Over the next four years, almost 15,000 children flooded into the Hospital, sending the House of Commons into a panic because of the expense.

With this many children, and this much anxiety over the cost of raising them, there followed trauma. Many children suffered at the hands of irresponsible wet-nurses and cruel employers, to whom they were apprenticed at 12 or 14. Others died from diseases – inevitable in the period, but probably exacerbated by such a dense child population. Occasionally, there was scandal: Elizabeth Brownrigg was a midwife who so mistreated her apprenticed servant girls that one died of the beatings and neglect received at Brownrigg’s hands. While this forced the Foundling Hospital to review its policies and the sorts of people to whom it sent orphans, it was far too late for many: of the almost-15,000 admitted between 1756 and 1760, just 4,400 lived to adulthood.

Over time, the Foundling Hospital attracted celebrity patrons, including composer Georg Frideric Handel and artist William Hogarth. With more money came better living conditions for the children, and it weathered the nineteenth century without major scandal. Yet it couldn’t hope to accept every homeless child in London. From what I’ve been able to learn, it still admitted mainly infants, which would exclude a child like my heroine, Mary Quinn, who loses her mother when she’s seven or eight.

The Hospital still exists today. It’s no longer in London – it moved to the countryside in the 1920s – but it leaves Coram’s Fields as a physical reminder of its existence, and of the tragic sights that inspired Thomas Coram.

Thank you, Ying! It's been a pleasure having you here!

Y.S. Lee is the author of the Agency books: The Spy in the House, The Body at the Tower, and The Traitor in the Tunnel, all from Candlewick Books.

When I lived in London, I walked past Coram’s Fields every day. It’s a beautiful park with a fountain, an urban farm (the sheep always look grimy, but London is a highly polluted city!), a ton of open space, and high gates. Most enticing of all to a curious adult is the sign saying, NO ADULTS UNLESS ACCOMPANIED BY A CHILD. I had to find out more, and since I didn’t know any children I could borrow at the time, it had to be theoretical research.

After basic details about the current park (www.coramsfields.org/), I learned that Coram’s Fields stands on the site of the old London Foundling Hospital – not a hospital in the modern sense of the word, but a charity orphanage. In the 1730s, sea captain, merchant, and philanthropist Thomas Coram became appalled by the number of homeless, dying, and dead children on the streets of London. There was no institution in England doing anything for illegitimate children – the usual reason for abandoning an infant to the workhouse or the streets. Coram persuaded George II to grant him a Royal Charter to establish a “hospital for the maintenance and education of exposed and deserted young children”. In 1741, the London Foundling Hospital opened in a temporary house and began accepting children. (Image above from the Foundling Hospital's website, http://www.foundlingmuseum.org.uk/)

After basic details about the current park (www.coramsfields.org/), I learned that Coram’s Fields stands on the site of the old London Foundling Hospital – not a hospital in the modern sense of the word, but a charity orphanage. In the 1730s, sea captain, merchant, and philanthropist Thomas Coram became appalled by the number of homeless, dying, and dead children on the streets of London. There was no institution in England doing anything for illegitimate children – the usual reason for abandoning an infant to the workhouse or the streets. Coram persuaded George II to grant him a Royal Charter to establish a “hospital for the maintenance and education of exposed and deserted young children”. In 1741, the London Foundling Hospital opened in a temporary house and began accepting children. (Image above from the Foundling Hospital's website, http://www.foundlingmuseum.org.uk/)It must have been a tragic process: parents brought their children, usually babies under one year old, along with a distinguishing item - a trinket, ribbon, or meaningful scrap of writing – that was kept with the child’s record in case the parent came back to reclaim the child. I can’t help imagining a parade of destitute adults, hoping to give their children a decent chance at life by giving them up (maybe temporarily) to the Foundling Hospital.

The demand for the Hospital’s services was enormous – so much so that it was forced to turn away unknown numbers of children. In 1756, the House of Commons resolved that all children should be accepted – not just from London, but all over the country. Over the next four years, almost 15,000 children flooded into the Hospital, sending the House of Commons into a panic because of the expense.

With this many children, and this much anxiety over the cost of raising them, there followed trauma. Many children suffered at the hands of irresponsible wet-nurses and cruel employers, to whom they were apprenticed at 12 or 14. Others died from diseases – inevitable in the period, but probably exacerbated by such a dense child population. Occasionally, there was scandal: Elizabeth Brownrigg was a midwife who so mistreated her apprenticed servant girls that one died of the beatings and neglect received at Brownrigg’s hands. While this forced the Foundling Hospital to review its policies and the sorts of people to whom it sent orphans, it was far too late for many: of the almost-15,000 admitted between 1756 and 1760, just 4,400 lived to adulthood.

Over time, the Foundling Hospital attracted celebrity patrons, including composer Georg Frideric Handel and artist William Hogarth. With more money came better living conditions for the children, and it weathered the nineteenth century without major scandal. Yet it couldn’t hope to accept every homeless child in London. From what I’ve been able to learn, it still admitted mainly infants, which would exclude a child like my heroine, Mary Quinn, who loses her mother when she’s seven or eight.

The Hospital still exists today. It’s no longer in London – it moved to the countryside in the 1920s – but it leaves Coram’s Fields as a physical reminder of its existence, and of the tragic sights that inspired Thomas Coram.

Thank you, Ying! It's been a pleasure having you here!

Y.S. Lee is the author of the Agency books: The Spy in the House, The Body at the Tower, and The Traitor in the Tunnel, all from Candlewick Books.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)