[I

originally penned this post 10 years ago around Valentine’s Day, but I thought

it was time to bring it to the forefront. Happy Valentine’s Day!]

[I

originally penned this post 10 years ago around Valentine’s Day, but I thought

it was time to bring it to the forefront. Happy Valentine’s Day!]

Valentine’s Day was eagerly awaited by many a young nineteenth century lass and lad in England. Thousands of Valentine letters were exchanged in London alone. In fact, the 1835 Post-Master General’s report cites an additional 50,000 or 60,000 pieces of mail through the London Twopenny Post around Valentine’s Day. The hundred or so letter carriers in London had to be given additional money for refreshments just to see them through their arduous work. In a bigger city, they might make deliveries as many as six times a day!

However, even with their help, figuring out how to get your Valentine from your fingers to your true love wasn’t for the faint of heart. You could hand it to the postman, if you caught him on one of his rounds, or you could take it to the Post Office near you, which could be at a shop or an inn if you were in a smaller town or village. Later in the century, post boxes appeared to collect letters in certain areas. Some villages didn’t even have post offices or boxes, requiring you to walk miles to post a letter or to take the chance of paying a private firm to deliver your message for you. Many such firms went bankrupt before letters were even delivered.

Then too, each sheet of paper cost money to send, to be paid by the person who received it. While England was at war with France, postage costs kept increasing. Postage was also higher the farther the letter had to travel. As you can imagine, the cost put a burden on the average working man or lady, not to mention the underemployed teen.

So,

letter writers got creative. Instead of using more than one sheet, they wrote

on both sides of the one, vertically, horizontally, and then kitty corner! Such

cross writing was notoriously difficult to read, particularly squinting over

candlelight. Then too, some friends or family who lived far apart arranged a

code. If a letter arrived from the friend with your name misspelled or perhaps

the address lettered wrong, why you knew that the friend was well and you could

refuse to pay for the letter. There were also tales of people writing with milk

along the margins of newspapers, which were free to mail, so that a friend

could read the note over the heat of a flame.

So,

letter writers got creative. Instead of using more than one sheet, they wrote

on both sides of the one, vertically, horizontally, and then kitty corner! Such

cross writing was notoriously difficult to read, particularly squinting over

candlelight. Then too, some friends or family who lived far apart arranged a

code. If a letter arrived from the friend with your name misspelled or perhaps

the address lettered wrong, why you knew that the friend was well and you could

refuse to pay for the letter. There were also tales of people writing with milk

along the margins of newspapers, which were free to mail, so that a friend

could read the note over the heat of a flame.

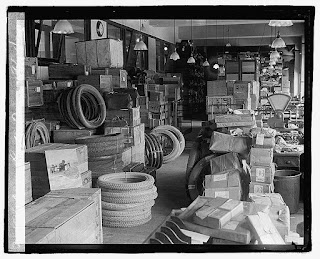

Letters

that were refused ended up in the Dead Letter Office. I can imagine it looking

something like the Library of Congress in Indiana

Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark, although this is what one looked

like in America in the early twentieth century. (Tires? Really?) Post Office employees often had to

open the mail to determine how else it might find it rightful home. But in the

early nineteenth century in England, Post Office employees were allowed to open

and read your mail under other circumstances too, such as if you were suspected

of being a traitor to England (“Dear Napoleon—I love you!”), evading Customs

(“Dear Aunt Charlotte, that case of Brussels lace is safely stored in the cave

under Peasbury Abbey.”), or involved in a robbery (“Dear Susan, I am delighted

to relate that I was able to make away with that diamond ring you always

wanted.”). If you were in jail for bankruptcy, the Post Office even sent all

your mail to the solicitor in charge of prosecuting the case!

Letters

that were refused ended up in the Dead Letter Office. I can imagine it looking

something like the Library of Congress in Indiana

Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark, although this is what one looked

like in America in the early twentieth century. (Tires? Really?) Post Office employees often had to

open the mail to determine how else it might find it rightful home. But in the

early nineteenth century in England, Post Office employees were allowed to open

and read your mail under other circumstances too, such as if you were suspected

of being a traitor to England (“Dear Napoleon—I love you!”), evading Customs

(“Dear Aunt Charlotte, that case of Brussels lace is safely stored in the cave

under Peasbury Abbey.”), or involved in a robbery (“Dear Susan, I am delighted

to relate that I was able to make away with that diamond ring you always

wanted.”). If you were in jail for bankruptcy, the Post Office even sent all

your mail to the solicitor in charge of prosecuting the case!

I’m just thankful for mail carriers today. They deliver author copies, fan mail, royalty statements, and all manner of things designed to make a writer’s heart go pitter-patter, even when it isn’t Valentine’s Day.

No comments:

Post a Comment